I’ve long been fascinated with nontraditional, “practical” applications of the hobbies that us nerds hold dear, especially when those applications can really do some good for people. When I worked in games and comics retail, one of my favorite projects involved reaching out to local libraries and schools to try to help them build graphic novel and tabletop collections, both because I think these are underserved markets and because I think that kids really benefit from having access to artifacts that inspire them to dream imaginative stories of their own.

One of the latest frontiers of this kind of application, at least as it’s come across my notice, is the therapeutic case for Dungeons & Dragons — or really, any tabletop roleplaying (but it’s often D&D, just because of its ubiquity). I love reading about how a fanciful game designed to encourage us to create wild fantasy stories can earnestly help people get out of their own heads and grapple with some of the problems that hold them back in real life. And it makes sense, right? It’s easiest to learn a lesson when it doesn’t feel like learning. Play is an incredible teacher.

I tend to collect articles about this particular phenomenon whenever they pop up in my industry news feeds, and I’d like to shout out a couple of my favorites:

This article on a virtual D&D therapy group, from Carbondale, IL’s The Southern Illinoisan, discusses how mental health provider Centerstone added a D&D service during the early pandemic to help people process difficult issues. Of the program, director Dani LaPlant says “A D&D group provides a safe environment for people to talk through and process relationship issues, grievances and successes, and can even help boost self-esteem.” As a press release about Centerstone’s offering notes, “the game provides an opportunity for increased mindfulness, as players think through their decisions as their characters rather than as themselves.” In other words, having the extra abstracted layer of a fantasy character that stands between a player and their issues allows a player to work through things with their character that they may struggle with in themselves.

More recently, researchers from James Cook University released a paper titled “A Study on the Efficacy of the Tabletop Roleplaying Game Dungeons & Dragons for Improving Mental Health and Self-Concepts in a Community Sample,” which says a lot right there! Since this is a clinical study, I’ll leave y’all to dig in if you’d like, but this note from the abstract sells the point: “Participants demonstrated significant decreases in depression, stress, and anxiety and significant increases in self-esteem and self-efficacy over the study period. As such, D&D may have potential utility as a wellbeing intervention or prevention program.” And like, that’s written on a site with .edu in the address. So you know it’s good shit.

I’ve seen the therapeutic aspect of tabletop roleplaying show itself in my games at least once very memorably, when I was running my ‘90s sitcom-inspired DIE scenario, “Empty House,” for friends last year1. I’ve talked before about how DIE is uniquely positioned to bring up tough feelings at the table, and even in a silly scenario like “someone in the cast of your Bush-era sitcom is mad that you never got rebooted, so she’s dragging you into a fantasy world where you do,” there was a moment when the game got real.

In this particular instance of “Empty House,” one of my friends — taking up the persona of the actress who played the cool elder sibling on our fake sitcom — decided to take inspiration for his character from Becky I from Roseanne, meaning that she was recast partway through the original run of the show with little explanation. Except whereas the real first Becky left for school commitments, in our version, my friend decided that she had been recast due to crippling addiction issues that took her out of Hollywood for a time.

Naturally, this being a game of DIE, I had to have my friend’s character confront a doppelganger recalling the actress who replaced her on the show, to really maximize the emotional weight of the persona’s conflict. The scene that resulted from this was way heavier than anyone anticipated, in a really wonderful way. My friend delievered a minutes-long monologue about being unceremoniously cast aside, about not feeling good enough and never even really getting the chance to process why or tell her story. It was truly moving stuff, and for a moment, the emotions at the table left the game world behind. This was real tabletop alchemy. Afterwards, my friend said he didn’t even know where those feelings came from, just that he accessed something super real for a moment, and it all came out. That cemented for me, if I wasn’t already sure, that roleplaying games have a serious power to explore issues that folks have maybe never even vocalized to themselves before.

When it comes to tabletop RPGs, I GM a lot more than I play, and when I do play, I’m really bad at coming up with characters. Some of that is analysis paralysis and some of that is just the way my creativity is wired. As my friend Jeremy told me he learned in improv training, there are three core aspects of improvisers — creator, builder, and connector. I think this ports nicely to tabletop roleplayers, and of those three aspects, creating is for sure the thing I’m worst at2.

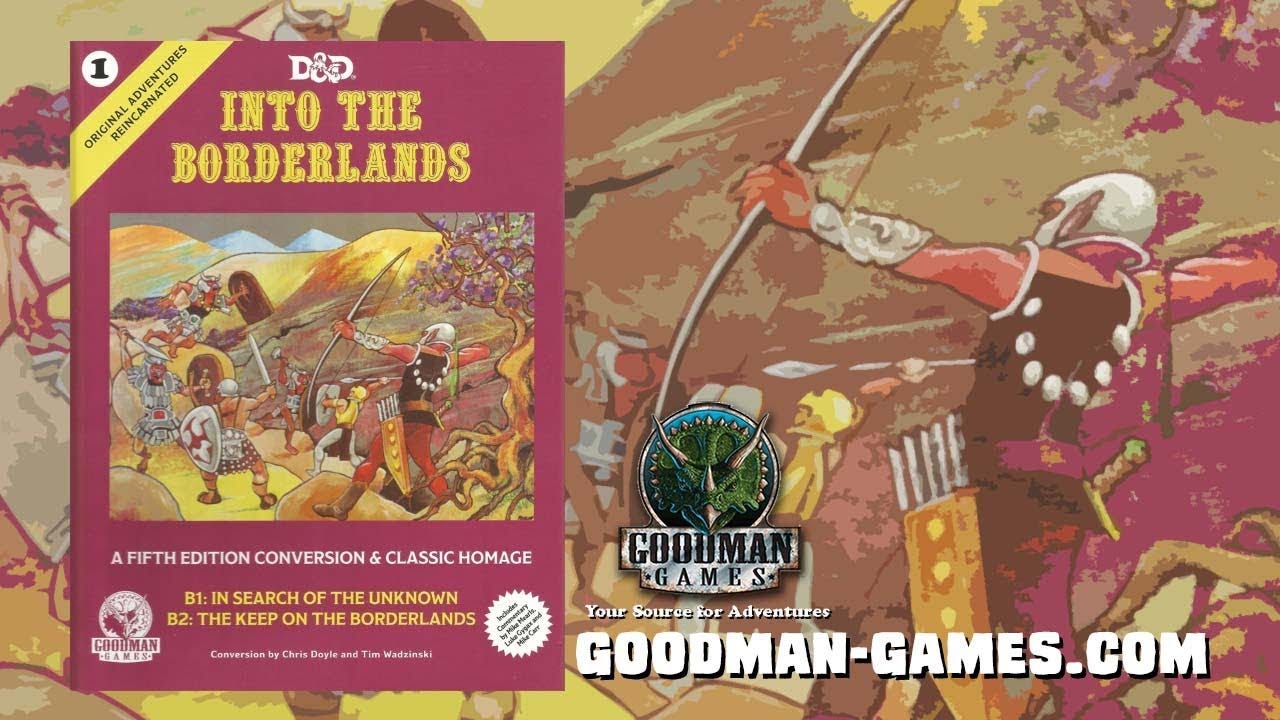

So when my friend Adam invited me to play in his campaign of Into the Borderlands, I had no idea what sort of character I should make. I took inspiration from another player in the group, who mentioned that they had based their character on an old Saturday Night Live sketch3. That got me thinking about what SNL characters might be fun to adapt to D&D, and after a couple days of consideration, I settled on a fantasy version of the gentleman pictured above, the one and only Matt Foley (played with utmost humanity by Chris Farley). Partially I think I got there because this sentence really made me laugh:

“I am Matteus Fölle, I am five-and-thirty, I am thrice separated, and I live in a wagon down by yon river.”

Matteus (half-orc bard) was a sweet, down-on-his-luck goofball who really tried to motivate people by telling them about his unfortunate circumstances, and he tended to lose his temper when things didn’t go his way. He wasn’t proud of that, mind you, and I actually tracked every time he lost his cool and made him take a level in barbarian if he pushed it (he didn’t want to).

I had a lot of fun playing Matteus. We didn’t completely line up emotionally, as I don’t really get filled with rage, but I do get frustrated, and boy, did the game give me opportunities to get frustrated. Into the Borderlands is a 5e adaptation of an early D&D module, which tend to be pretty punishing, especially when you start at level 1 like we did. Adam was an incredible gamemaster, truly he gave me the most fun I’ve ever had in the players’ seat, and he was exactingly fair about which characters would encounter fate’s cruel whims: in the event of a trap, sneak attack, ambush, etc., where there was no reason to prioritize any player taking damage over the others, he would roll a die to randomize a target. And almost every time, that die would decide that ol’ Matteus was the victim. I truly think I got KOed three times before I hit level 2. Matteus was starting to feel like the world was out to get him, because it kind of was.

But, you know, “whatever doesn’t kill you….” Fighting through his misfortune and shaking off embarassing defeats, Matteus got better, stronger. He added some levels, gained some hit points. Processing his experiences, his motivational speeches actually started to work on some folks. He got closer with the people in his party and found successes in a group that he could never have found alone. He stopped losing his cool, stopped feeling like the world was out to get him, even if luck didn’t go his way. Sometimes he made his own luck, and sometimes he just rolled with the punches.

And then, the final battle of the campaign. God, this was epic; it really came together like a film. In the end, Matteus was the only character left standing against the evil wizard Marevak, one hit away from death, options super limited. He wanted to run. But instead, Matteus said “fuck it, we’re doing this.” He charged at the wizard, through obstacles and enemies (avoiding an opportunity attack that would have dropped him!), swung with his greataxe, and — critical hit. Double damage. The wizard fell, head cleaved in two. His allies retreated. The heroes had won. Back against the wall, one hit from death, Matteus — a dude who, a few weeks prior, had been the brunt of every attack, had dropped in fights in the first round — ended the campaign with a crit. It was incredible. He and I celebrated together.

Ultimately, while I didn’t feel a 1:1 connection to Matteus, there definitely was something that attracted me to playing an aw-shucks, down-on-his-luck creative who was stuck on questioning his value. It was fucking cool helping Matteus find his mojo, enough to make a heroic last stand against the Big Bad and come out the other side. Matteus got his happy ending by journeying with his pals, honing his talents, and believing in himself. That’s a pretty good-feeling story to take back to reality.

Next week — for the first time in my life, at 40 years of age — I’m starting therapy. I’ve rarely had the money/insurance to afford it before, and when I did, I didn’t have the time. But now, stuff with the day job has lined up in such a way that I very fortunately have both.

As you may have gathered from reading this newsletter, it’s been a tough summer, and the feelings brought up by the experiences I’ve mentioned here have been heavier than I was expecting (although maybe there were some signs right in front of me that I could use some work on myself). I need to learn some of the same lessons Matteus did. Maybe I can use some of the experience from Adam’s game to help me.

Thinking about talking to a therapist for the first time puts me in a weird headspace. I’m excited, for sure — I actively want to get better, and I feel strongly that I’ve reached the limits of what I can do without professional help. But I’m also tripedatious. I’m a little scared that the experience may be too hard, or uncover too much I’m not ready for, or alter me in some way I won’t like. I think these are all natural feelings, and they’re not going to stop me from doing the thing, but I do feel it’s important to express them.

What’s kind of funny to me, though, is that all those thoughts — even the very metaphor of investigating myself — kind of make me feel like I’m about to go dungeon-diving, you know? Like, I better stock up on supplies and rest in the nearest town, because I’m going to be plumbing some depths, and it might indeed be hard, scary, isolating at times. Good thing a lifetime of gaming has shown me how to equip for that kind of journey, and that with some work and perseverance, the heroes come out victorious on the other side.

I started this post by talking about how D&D can be therapy. I also think that maybe therapy can be D&D. Here’s to leveling up.

BTW, for anybody going to Madison, WI’s Gamehole Con in October, I’m running this game on Friday night. There are still 2 tickets left but it looks sure to sell out! I’m also running one of my patented Saved by the Morph modules, which at the moment has zero tickets sold, lol.

I have a draft of a post diving deeper into this topic, btw. I think it’s a pretty neat topic!