What do the X-Men and Jennette McCurdy have in common?

30 years apart, two pieces of media helped me make peace with having a bad parent

I can tell you the exact day my dad walked out on my mom and me. Not because I have some kind of superhuman recall for calendar dates, but because it was the same day Batman: The Animated Series premiered on TV. On Sunday, September 6, 1992, Fox was doing a special primetime airing of the B:TAS pilot, “On Leather Wings,” before the show’s debut in its weekday afternoon time slot the next day. I was soooo hyped to see this first glimpse of something I was destined to love, but unfortunately my evening plans were displaced by my dad deciding he didn’t want to be at home anymore. (I had to catch “On Leather Wings” on a later weekday rerun like some kind of normie.)

A few weeks after that, on Halloween 1992, another superhero cartoon premiered on Fox’s Saturday morning lineup that would blow my 8-year-old brain.

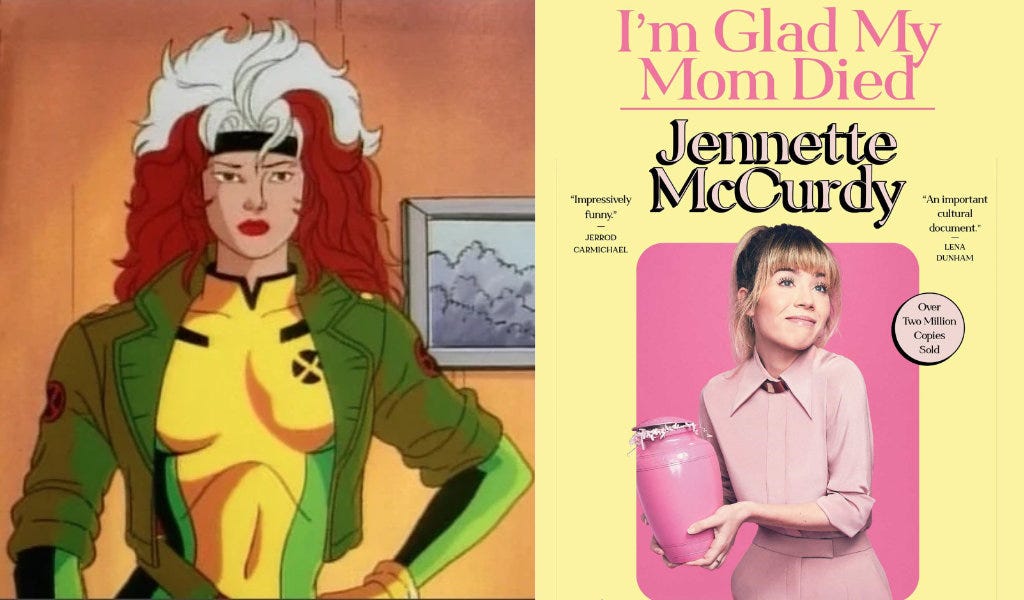

Over the past year, I’ve gotten really into listening to audiobooks on long solo road trips. When I drove to Louisville and back for the GAMA expo a couple weeks ago, I decided to hit play on Jennette McCurdy’s I’m Glad My Mom Died, a super acclaimed nonfiction piece from 2022 that you can probably guess the subject matter of. This was recommended to me by my friend and former Mortified Chicago coproducer Katie, which makes sense because it’s kind of the dark side of the stuff we explore in Mortified — what happens when your adolescence shoots beyond cringey and awkward to abused and exploited.

(I’m going to try to talk sensitively about this, because unlike the other subjects of this piece, McCurdy is a real person, and I want to respect her story. More than that, I want to respect her telling of her story. Be warned, some rough topics will be covered.)

I’m Glad My Mom Died is McCurdy’s memoir; it details her career as a child actor and delves into the depths of the ways people in her life took advantage of her in that career. What really struck me is how much McCurdy’s adolescence lacked any facet over which she had control. I mean, most of us don’t have a ton of control as kids, but (hopefully) most of us don’t also become cyphers for the desires of others. McCurdy’s mom pushed her into acting because it had been her dream, then bestowed upon her an eating disorder in a fucked up attempt to keep her looking castable. Her showrunner trapped her in a toxic work environment by dangling carrots that never materialized. An early boyfriend manipulated her into her first sexual experience. It really hurt to hear all the ways people used McCurdy for what they wanted, giving no care for her own wants. Spoiler here: one of the major breakthroughs of McCurdy’s book is that writing gives her some of the control and power she’d been lacking elsewhere, which is why I’m Glad My Mom Died comes to be.

As it happens, at the same time I was listening to I’m Glad My Mom Died, I was in the middle of an X-Men: The Animated Series rewatch to prep for X-Men ‘97. Engaging with both at the same time led to parts of the two narratives intermingling for me. In particular, I’m Glad My Mom Died helped me articulate something that I’d felt since I was myself an adolescent: that X-Men was probably the first media I loved that wanted to tell me that sometimes parents are bad.

Over its 60-plus years, the X-Men franchise has meant a lot of things to a lot of people. This is by design: although its very first incarnation was intended as a response to the twin 1960s vibes of social revolution and nuclear fear (which is why it originally starred five of the WASPiest teens imaginable)1, when the comic was relaunched into the All-New, All-Different X-Men in 1975, writers Len Wein and Chris Claremont specifically set out to make the team multicultural and multinational, to push the metaphor of mutants as objects of prejudice into the real world. These days, X-Men stories pretty famously function as metaphors for LGBTQ+ struggles as well, thanks in large part to Bryan Singer’s films (let’s not thank him for much else). Generally speaking, because the central X-Men metaphor is so broadly abstracted, lots of people have the opportunity to see their feelings of marginalization reflected in its colorful presentation.

As a cis straight white guy, I think I can rightly say that a lifetime of X-Men fandom has helped grant me empathy for people that society marginalizes. But McCurdy’s book helped me articulate that X-Men helped me feel seen, too, in a way I hadn’t realized.

Now, I grant you, I probably wasn’t consciously thinking about how boldly X-Men showed abusive parents in 1992 (although there’s no way I missed some of the biggest swings, like the constant flashbacks to Rogue’s dad throwing her out of the house). By the time Fox was re-airing the show post-Singer film in 2000, though, I certainly was, because by then I was a hormonal adolescent too, and things with my dad had gotten worse.2

Still, it took the eyes of an almost 40-year-old adult in 2024 to pick up on some things I wasn’t sharp enough to get at 16. For instance: in the pilot episode, “Night of the Sentinels,” the X-Men take in a runaway mutant teenager (Jubilee) who’d been living with foster parents. At one point, Wolverine asks the team if anyone tried to call her parents. Rogue responds “We gave ‘em a holler, but nobody hollered back.” I must have watched this episode three dozen times as a kid (thanks to my VHS tape scored from Book It rewards, natch), and I always thought that just meant her foster parents weren’t home. I realize now of course that, no, they just didn’t want to answer.

There’s a four-episode run in the fourth season that addresses parenthood head-on, which I happened to watch the same weekend I finished McCurdy’s book. Man, was that a cocktail of emotions. I don’t know whether X-Men’s showrunners specifically grouped up thematically similar episodes, but it was a little bit of an onslaught (pun intended?) to get through them; I was buouyed only by the fact that one of the episodes is pretty bad, so it didn’t hit as hard as it could have.

First up, in the two-parter “Proteus,” the X-Men are called to Scotland to assist with a mutant adolescent named Kevin whose incredible powers can bend reality with a thought. Kevin is too dangerous to be out in the world, but his mom (Moira McTaggert) and her boyfriend Sean Cassidy (the Banshee) try to help him at their Muir Island research facility. Unfortunately but understandably, Kevin longs for the affection of his biological dad, who happens to be a Scottish politician running on a family-first platform (with his second family). Though I found the end of this episode a little cheap (Kevin’s dad has a change of heart about his mutant son once Professor Xavier helps him bring his powers under control), I thought the premise was fascinating on a couple levels. “What do you do with a mutant too young and emotional to control his powers?” is a great question for The Metaphor, and “how is a teenage boy expected to navigate the complicated feelings of family and belonging with a hypocritical scumbag of a dad who’s moved on?” is full of good drama — and, for me, relatable.

Then comes “Family Ties,” one of the weaker entries in the series, which involves a ridiculous character called The High Evolutionary and his city of sentient cow-people. Okay. (X-Men loses some of its charm when it stretches too far into sci-fi IMO.) The part of this episode I did like, though, is that it centers the relationship between antagonist Magneto and his children Quicksilver and Scarlet Witch, who learn about each other through the events of this story. At the end of the episode, Magneto (one of my favorite characters in the series, due mostly to the vocal performance by David Hemblen, who has sadly passed) expresses great reget to his children about his absence: “If I had known about you, I would have been there.” Quicksilver coldly replies: “I guess we’ll never know,” and that’s where the episode leaves it. This one almost does the inverse of “Proteus” — most of the story is pretty mindless, but it ends on a really powerful note that resists the easy reconciliation lesser shows would have foisted on us.

Finally, there’s “Bloodlines,” my favorite of the four. This episode, in which the domestic terrorist group Friends of Humanity orchestrates a plan to capture the devilish-looking but kindhearted Nightcrawler, dives into the super complicated familial bonds of shapeshifter Mystique, who, as we learn in this ep, gave birth to Nightcrawler while she was masquerading as a European countess. Given Nightcrawler’s wicked appearance, Mystique’s status as a mutant was revealed, so she abandoned her baby to the elements and took off to find a new grift to start. When Nightcrawler learns the truth, he strives to understand his mother’s motivations, but she’s intransigent, even mocking: “How do you feel knowing your mother never wanted you?” Nightcrawler, who ended up being found and raised by an order of monks, gives the following reply: “First, I will pray that God grants me the strength to forgive you. Then, I will pray that He grants you the grace to forgive yourself.” Heavy!! Not only does no parental reconciliation happen in this episode, but as a final impression, the story’s antagonist (Friends of Humanity leader Graydon Creed) is left to suffer at the hands of his own abusive father, Victor Creed, aka the villainous mutant Sabretooth. Yeah — this episode ends with a strong implication that Creed’s comeuppance will be delivered by his dad getting another shot at him. Certainly a, uh, mixed bag of emotions there.

The narrative society likes to tell about parents and their children aims to stamp out any negative feelings between them. This invades even in my personal interactions; unless I’m talking to one of my closest friends, it’s not uncommon for someone to hear about my feelings towards my dad and say some variant of “oh, well, you’ll probably want to make peace with him before he dies. He’s your dad, after all.”

This strikes me as a really unhealthy knee-jerk reaction to someone’s feelings, and it’s why I appreciate both the X-Men and Jennette McCurdy’s book so much. I mean, in theory the X-Men aren’t offending any real-world people with their “don’t trust every parent” stance, so I guess McCurdy gets a bigger W on this one. I truly think it’s brave of her to have written I’m Glad My Mom Died for a number of reasons, one of them being that the title echoes a sentiment that a lot of people don’t seem ready to hear. But for those of us who are already suspicious of our parents, it’s super validating. It feels like her book, with all its success and accollades, genuinely makes it easier to have these conversations with people. Maybe now a few less folks will automatically assume I’ll want to make nice with my dad before he dies. Maybe some of them will understand that sometimes, there’s no winning to be had there.

You know the common criticism that superhero stories are just adolescent power fantasies in disguise? Well, since McCurdy’s journey through adolescence is one about claiming power for herself against difficult odds, that kind of makes her seem like a superhero to me. Lucky for me, I found a power in hearing her words, too.

When I was 8, or 16, and I saw a scene of Rogue’s dad throwing her out of the house, I know how uncomfortable yet seen that made me feel — and I know that X-Men released that emotional tension by then having Rogue beat up on the Sentinels, or Apocalypse, or whoever was the villain of the week. Which, honestly, is super effective; I’m not sure what else you could want from a kids’ action show.

Now, at 39, I recognize that there aren’t such easy releases in real life; McCurdy’s book doesn’t end with a flashy battle scene but instead a direct acknowledgement, for the first time in her whole story, detailing her mom’s abuse. It’s a different kind of release: the release of vocalizing your feelings and learning to live with them. The struggle continues, but you’re in a better place to take it on.

Different vibes for sure, but it was nice, as an unintentional companion piece to McCurdy’s book, to revisit a cartoon that meant a lot to me, and to be able to vocalize for the first time a key reason why. That’s the thing about making media, I guess — you never know how people are taking it in. X-Men allowed lots of kids to see themselves in the colorful heroes on screen. I think sometimes we need power fantasies like that — sometimes they help us find power in our real lives.

~~The Plugs Section~~

My friends made a TTRPG inspired by children’s play mats, Goosebumps, and the terrors of suburbia called That Rug, and I’m helping to publish it! It’s going live on Kickstarter soon; click that link to hit up the pre-launch page and give us a follow!

The next Mortified Chicago show is Saturday, May 18 at the Studebaker Theater and it’s going to be sweet!

There are a lot of great essays about the X-Men’s not-super-identity-based beginnings in The Ages of The X-Men, a collection of peer-reviewed pieces published by McFarland in 2014, which I happened to contribute to, lol

I want to be clear that there was no physical violence here. Emotional neglect and cruelty only, baby!

I love when this happens and we find two pieces of content that seem to pair so well with something we’ve had in our thoughts. I had an absent mother my whole life so I think about that a lot more as a parent myself now and so much of what I consume strikes me so much harder as a parent. Going to check out that memoir, thanks for writing about it, dude, always love reading your stuff

Thanks for sharing! I prepared for xmen 97 recently by rewatched the original series as well. Something it also does rather well is showcase the positive benefits of found family. It's interesting how 90's cartoons had themes they hit you over the head with a hammer and at the same time provided softly served themes that they let slide it casually.

Again I super appreciate your take and sharing of personal connections with loved media. Great work!