[Content warning: The first segment of this piece contains a brief but tough mention of abuse.]

The Real World (Melissa Benoist, 2015/9)

“I just had this injury so I had this eye patch on. It was kind of embarassing,” actress Melissa Benoist told E News in 2015 about her first time trying on the Supergirl costume. “But the second I put it on, something shifts inside of me. It’s kind of impossible not to feel strength and empowerment and positivity and hope.”

Four years after this interview, Benoist would reveal that, around the time her Supergirl show was starting up, she was trapped in a violently abusive relationship, and it’s very likely that the eye patch she was wearing in the above story came from her then-partner throwing an iPhone at her1.

In an Instagram video where Benoist shares her story, she credits a friend with helping her break out of this abuse; in her words, during a set visit away from her partner, her friend spoke hard truths about what she was seeing, and it helped spark the catalyst for Benoist to get away. And while this is obviously Melissa’s story to tell, and she doesn’t explicitly mention the Supergirl costume in her video, I can’t help but think of her earlier words about trying on the costume during this awful time: “Something shifts inside me.”

JLA One Million (Grant Morrison & Howard Porter, 1998)

The 1990s are under siege from the far future! On the eve of Superman Prime’s return, the greatest threats of the 853rd century2 have concoted a plan to snuff out the universe’s most iconic dynasty of heroes at its beginning. As part of their scheme, they unleash a plague of madness onto the Earth that overwhelms 1998’s primitive antibodies. Only the remnants of the Justice League, secured in their Watchtower on the moon, are protected. But the heroes of the future — the same ones who (unwittingly, they say) brought the virus back in time — demand the Justice League grant them access to their stronghold, so they can work together to save all of existence.

At the crux of this crisis, John Henry, aka Steel, de facto leader of the remaining League, delivers a killer speech to the Superman of the 853rd century:

I could have activated the secure systems I’ve been installing: EM pulses, neural wipes, genetically targeted atomic bullets. And I have the world’s greatest superheroes right here at my disposal. I really think we could have beaten you; all I had to do was press the button. But then I thought about it for a minute. You may be the future JLA, but you’re still the JLA, and the JLA is all about saving the world. And I thought “What would my JLA do in your shoes?” Then I made one of those hard decisions. There’s an “S” on that costume of yours somewhere too, so I’m guessing you know exactly what I’m talking about.

The first time I read this comic was, for me, the first time I really clocked what that S could mean.

This is but the first mention of Grant Morrison in this piece.

South Park, “Imaginationland” (Trey Parker & Matt Stone, 2007)

I’m not much of a religious guy; the closest I come to believing in powers beyond us on a regular basis is reflected in Kyle’s monologue in the three-part “Imaginationland” episodes of South Park, in which the kids become aware of a terrorist threat to destroy our imaginations and have to convince the US government not to bomb and destroy that imagination in response (lol). To get them to understand the stakes of their violence, here’s what Kyle says:

It’s all real. Think about it. Haven’t Luke Skywalker and Santa Claus affected your lives more than most real people in this room? I mean, whether Jesus is real or not, He had a bigger impact on the world than any of us have. And the same can be said for Bugs Bunny and Superman and Harry Potter. They changed my life, changed the way I act on the Earth. Doesn’t that make them kind of real?

Kyle has some good company in feeling this way.

The Real World (Grant Morrison, the 1960s)

It should be no secret that I consider Grant Morrison the definitive writer of superhero fiction, and one of my favorite authors of all time. They have an entire body of work extolling the real powers of superheroes (some of which I’m referencing in this piece), but there’s one quote of theirs that comes up time and again, in regards to the atomic bomb, that I think is instructive here. I’m taking this version of the quote from the 2011 documentary Talking with Gods. Important background here is that Grant’s parents were heavily involved in anti-nuclear activism in Scotland.

I just lived daily with the fact that my parents were fighting against the bomb, and the minute this thing happened, we would be obliterated forever. And for me the big thing was discovering superhero comics. Superman could take an atom bomb on the chest and just smile and shake it off. Before it was a bomb, the bomb was an idea. Superman's an even better idea. So why don't we make that one real?

Yeah, why don’t we?

All-Star Superman #10 (Grant Morrison & Frank Quitely, 2008) / The Real World (Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster, the 1930s)

Lex Luthor has fatally poisoned Superman, and the Man of Steel is going to die. Before he does, he’s determined to do as much good as he can on Earth — but he also wants to make sure humanity can survive without him. So, in true Superman fashion, he creates an “infant universe,” Earth Q, and watches it develop in compressed time, to see what a world without Superman would look like.

All-Star Superman #10 cuts to Earth Q for a handful of single panels throughout its pages: first, we see Austrlian Aboriginals make cave paintings of divine beings as they watch the stars. Then, a Hindu person carves a statue of Krishna. Later, Italian philosopher Giovanni Pico della Mirandola delivers an excerpt from his speech “Oration on the Dignity of Man,” which I too will excerpt here:

Let us not yield sovereignity even to them, the highest of the angelic hierarchies! Become instead like them in all their glory and dignity. Imitation is man’s nature and if he but wills it, so shall he surpass even imagination’s greatest paragons.

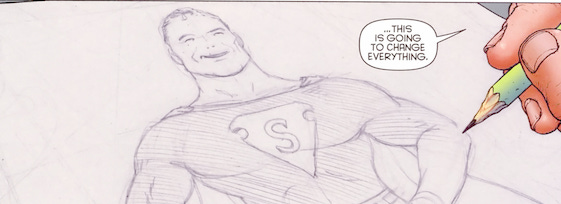

Later on Earth Q, we see Friedrich Nietzsche composing Thus Spake Zarathustra (“Behold, I teach you the Superman”), and finally, in 1930s Cleveland, a cartoonist sketches a recognizable symbol.

The point here being that, if Superman didn’t exist, humanity would make him themselves. And that’s exactly what happened.

By the way, All-Star Superman #10 is also the comic that contains the famous page that makes its rounds every World Suicide Prevention Day — a page that is on record as saving at least one life.

Real Life (me, 1984-present)

For a large part of my life, Superman wasn’t my favorite superhero. In fact, I wasn’t even that big a fan of the guy. I think this is pretty common for youth who think they have cool opinions on nerd stuff (trust me, I didn’t think anything else about me was cool, but I thought I knew my superheroes). I didn’t really watch Superman: The Animated Series the way I did Batman; I’d catch episodes here or there but it wasn’t appointment viewing for me. When the Justice League cartoon came out, I remember thinking, well, Superman works as a counterpoint to the rest of the team, because he can pretty much do anything, so he gives you a scale against which to measure threats, but he’s not interesting. You know, that old chunk of nonsense.

It actually took the aforementioned All-Star Superman for the character to really get his hooks in me. I was already sold on Grant Morrison from their runs on JLA and New X-Men, so I was down to read anything they wrote. If that meant picking up a monthly Superman book for the first time in my life, I was gonna do it!

And pretty quickly, All-Star just had me — with its cleverness, its charms, its art, and its heart. The storytelling is top-notch Morrison and there’s also so much humanity to it. When Clark travels back in time to spend an extra few minutes with his dad before he dies… you will believe a man can cry. With his heartfelt feats, Superman got to me, too.

I think a lot of people get this feeling out of All-Star, and it makes sense when you hear Grant talk about Superman:

We’re all Superman in our own adventures. We have our own Fortresses of Solitude we retreat to, with our own special collections of valued stuff, our own super-pets, our own “Bottle Cities” that we feel guilty for neglecting. We have our own peers and rivals and bizarre emotional or moral tangles to deal with. I felt I’d really grasped the concept when I saw him as Everyman, or rather as the dreamself of Everyman. That ‘S’ is the radiant emblem of divinity we reveal when we rip off our stuffy shirts, our social masks, our neuroses, our constructed selves, and become who we truly are.

Superman grew up baling hay on a farm. He goes to work, for a boss, in an office. He pines after a hard–working gal. Only when he tears off his shirt does that heroic, ideal inner self come to life. That’s actually a much more adult fantasy than the one Batman’s peddling but it also makes Superman a little harder to sell. He’s much more of a working class superhero….

If you know me, you know how much I love metatextuality. I was so drawn to the idea that Superman was just an amplified regular guy in a way that a Batman never could be. This feeling was kind of why I read comics in the first place. Grant’s Superman made me feel like I could do anything, be my best self. But what constitutes “best”?

Scott Hasn’t Seen, “The Passion of the Christ (2004)” (Scott Aukerman & Shaun Diston, 2022)

Scott Hasn’t Seen is the only film podcast I listen to, largely because I’m a giant Scott Aukerman stan and his sense of humor has come to define mine. But behind the show’s comedy, there’s also a ton of super astute media analysis. Scott is an incredible writer who understands story structure in a way that inspires me, and every so often, an episode of this very silly podcast blows me away.

The show’s Passion of the Christ episode is my favorite example. I can’t link it here because it’s behind the CBB World paywall (which, trust me, is absolutely worth signing up for), so you’ll have to trust my recap of Scott and “Sprague”’s analysis. Through the course of discussing this film, which is noted for its emphasis on the dark, violent, ugly parts of Jesus’s story, the hosts hit on something that blew my mind — that the philosophy driving the creation and reception of The Passion is the same one that drives the dark and violent comic book films produced by Zack Snyder.

Scott: [Passion director Mel Gibson’s] doing a lot of Snyder-esque slow-mo, and I was like, wow, this is a lot like Batman v. Superman. But then I started going, this movie is like the Batman movies. Fans of this character, they’re like, “hey, that’s my guy, from my stories, he’s up on screen! Oh, I finally get one that’s grim and gritty and true to how violent it is!

Shaun: It also had me thinking of the new Star Wars, right? The fandom of the new Star Wars is pretty toxic.

Scott: Yes, and it’s almost like a religion in how much they harass people who don’t believe what they believe. And it comes out of a place where something about it moves them. The lessons in this movie are very meaningful, and then it turns into a way of life for people. At a certain point it turns into this toxic thing. The Snyder people are like this too — “now I’m actively searching on Twitter for mentions of Snyder” and posting memes about “oh, you gonna cry?” if someone says they don’t like the new Snyder film. It’s turned into actively toxic fandom.

I’ve been thinking about this in relation to the backlash against James Gunn’s forthcoming take on the Man of Steel. A ton of the cultural conversation around 2025’s Superman relates to its tonal distinction from the DC movies that came before; in contrast to the drab, militaristic, and super-serious films of the Snyderverse, Gunn’s been very open about his more colorful influences (including All-Star Superman!) and how they’ve led to a gentler, brighter Superman.

Superman wants kids to not be afraid of him. He’s an alien. He’s got these incredible powers. He shoots beams out of his eyes, can blow a truck over. He’s this incredibly powerful, could be considered a scary individual, and he wants people to like him. He wants to be a symbol of hope and positivity. So he dresses like a professional wrestler, he dresses in a way that makes people unafraid of him, that shows that positivity.

This more pleasant thinking has engendered some real negative feelings towards Gunn from some not-so-pleasant people. And I can’t help but connect it to Scott Aukerman’s argument: that a certain subset of modern person (mostly Dudes) equate violence with seriousness, either because they think it’s more “real,” or perhaps because some even find it aspirational. They want their Jesus and Superman stories bloody and mean because that’s the energy they put out into the world. They don’t just see meanness as a fact of life — they actively curate their lives to make that the case.

The Real World (all of us, forever and ever but especially now)

I’ve been thinking about this sort of energy a lot in the wake of the election. My buddy Mike posted a really interesting article about the recent MAGA tide entitled “A Disease of Affluence” that I’m going to link here. While the site it’s hosted on is perhaps a little lecture-y for me, I think this piece makes some really illuminating points about the draw Trump’s philosophy has, specifically relating to how it’s one of superiority born out of anger:

While white supremacy, and white feelings of grievance, are clearly a big part of the new right, that’s not quite the through-line I’m drawing here: the desire is to always have someone beneath you as much as it is to maintain a place at the top. … In all the groups Trump gained with (young people, Hispanics, middle-income) most of the defections came from men. I think anger (sometimes self-aware, often subconscious) at women increasingly succeeding in the world, not always being beneath men socially, is one of the big things that attracts people of all backgrounds to Trump. Finally, economic position itself can be a source of dominance. The feeling of anger at a door-dash driver charging $20/hr for their time, or at service staff who are not desperate, or anyone you feel is beneath you claiming some dignity for themselves—that is not unique to any group of people. It is sadly just human.

Now, let me back up and say that I am absolutely not trying to imply that everyone who likes Man of Steel, like, actively creates this reactionary stratifying of society. But I do think, in general, the kinds of impulses that have driven the harsh discourse around the Gunn Superman film are the same ones that keep this stratification in its place, impulses born out of anger and resentment. The question is, what are those impulses in service of?

The Real World cont’d (still us, still now) / Green Lantern & Superman: Legend of the Green Flame (Neil Gaiman & Eric Shanower, 2000)

Capitalism is violence. This is something I take as a given. This operates in degrees, of course, and the connection isn’t always obvious, but then sometimes, it really is. It’s just a matter of when we call that violence terrorism and when we call it good business.

Violence is, without a doubt, a trope of the superhero genre (which is itself a sub-genre of action, which arguably can’t exist without violence). But there are still questions to interrogate here: against whom is violence deployed? When? Are there other solutions to consider?

Perhaps you’ve noticed — in every Superman story I’ve quoted above, both real and fictional, Superman stands in opposition to violence. For Melissa Benoist, the S (perhaps) helped glimpse a person with the power to leave an abusive relationship. For Steel, the S kept him cool in a crisis and made him realize that working with is better than working against. For Kyle Broflovski, the S helped him convince the US government not to blow up our imaginations (again, lol). For Grant Morrison, the S was a shelter from the atomic bomb. For Regan, the S was a warm hug that kept her feet planted. For Earth Q, the S put a capstone on centuries of philosopher-artists trying to show humanity a path beyond our worst instincts.

It has been discussed to the point of exhaustion that superhero stories are power fantasies. But again we can ask, whose fantasy do they support? And what would we do with that power?

Quoting a different comics author for a change, an image that’s stuck with me is Neil Gaiman’s concept of Superman in Hell, borrowed from an abandoned Alan Moore script. In a story entitled Legend of the Green Flame that was lost to editorial mandate in the 1980s but resurrected in 2000, the Man of Steel ends up in the underworld, and his torture is not that he must battle through hordes of demons or be subsumed in a lake of fire or whatever — it’s that he can hear the screams of every single suffering soul around him, and he can’t do anything to save them.

Fuck Neil Gaiman for his abhorrent behavior, but this one-page encapsulation of Superman has stayed with me for over two decades, coming to define the character for me along with his All-Star hug. If superheroes are a power fantasy, Superman is the ultimate one, and with all his power, the thing Superman wants to do more than anything is save everyone he can. Like Grant Morrison said, he’s our ideal self radiating out. That is, pardon the pun, a hell of a fantasy to have.

The Real World (us and our bank accounts, since the Reagan admin at least) / Action Comics (Grant Morrison & Gene Ha, 2011-3)

You might be thinking to yourself, hey, it’s pretty hypocritical of you to talk about how capitalism is violence while extolling the virtues of some giant piece of IP. Isn’t Superman just another example of corporate nonsense?

And hey, you’re not wrong! To that I’d say, there is even a Grant Morrison Superman story about this very idea; their Action Comics run from the New 52 features a Superman from a universe where heroes are Brands who ends up running amock because other versions of Superman don’t stay On Message.

And, look, unfortunately it’s pretty tough to find any popular art that isn’t beholden to some degree of economic interests. Eventually we’ll need new symbols, and we may even get them, but for now a large vector for conversations around cultural values is superhero movies, and so, reductively, I’d rather see superhero movies that I want to see! And even given the economic interests behind it all, I still think Superman has something important to say to us.

The Real World end (us and me, now and forever - or until climate change gets us) / Superman teaser (James Gunn, 2025)

I’ve talked about how some people find an aspirational Superman in a guy who just wants to save everyone he can, and how some people find an aspirational Superman in a guy who uses his power to beat up people he doesn’t like and make sure power structures aren’t challenged in any radical ways. And, here’s the twist — I think a lot of people hold both images of Superman in their mind, and I think most of us who like the character participate in both to varying degrees, just like we all participate in capitalism every day, say by buying comics or tickets to David Zaslav-produced megaplex-busting films.

Fuck, dude, I liked Man of Steel when it first came out. Don’t you go looking up my Facebook posts from that time, now.

But when I think about why Superman truly resonates with me, I think about what I wrote above. I think about Melissa Benoist, and Earth Q, and Regan, and Grant Morrison. I think about how Superman represents our ability to imagine the best, most powerful versions of ourselves. I think — or I hope — that if I had the kind of power he does, I would use it to save people whenever I could. And I have to admit that that is a fantasy, because I could do more now. But I also have to admit: I do have power. More than I think, probably. And Superman makes me think about how I could use it to help. I want to help.

So anyway — I really liked the teaser for James Gunn’s Superman. I’m ready to be inspired. I hope this is the Superman I need. But if not — we’ll just make him next time.

Apologies for linking to a gossip site here; it’s the only source I could find that made the timeline link explicit. I remember making this connection vividly when Benoist shared her story, but I must have put it together on my own.

Because Grant Morrison figured out that that’s when all our favorite comics would have their one millionth issues published, of course.

His "S'" is the basic reason why the majority of superheroes carry a similar insignia on their chests (at least, the ones I write about do)- they are continuing to do His work even as He continues to remain relevant.

I've always loved the lense superman provides. The best symbol of what humanity has to offer is reflected in the acts of an alien. It's so similar to how the idea of the American Dream can be best reflected in the acts of an immigrant.