Summoning Up a World: Springsteen's Debut at 50

My ode to Greetings from Asbury Park

Note: This essay was originally written to be read alongside a live performance of the songs off Greetings for the Solo Sunday series in Chicago. Since everything I post here has something to do with narrative, I thought this was relevant — it’s a look at how Bruce Springsteen went about laying the groundwork for the universe of his career, and why I think we can all learn something from that.

Fifty years ago, on January 5, 1973, Bruce Springsteen’s debut album, Greetings from Asbury Park, N.J., was released to the world. It didn’t enter the Billboard charts for two years. Rolling Stone didn’t even mention the record until July of ‘73, six months later. And yet this unlikely release, which could have easily washed out with the early 1970s tidal wave of “new Dylans,” ended up launching one of the most celebrated and impactful careers in all of popular music history.

Though Greetings forever lives in the shadow of the gigantic success of Born to Run – in fact it rode Born to Run’s coattails into the charts, peaking at #60 – looking at the record on its own reveals a revolutionary artist at the explosive start of his career. Just like an explosion, it’s loud, exciting, and uncontrolled. A recent retrospective on the website Albumism by Jeremy Levine summed up Greetings by saying: “it’s singular in the Springsteen oeuvre… because it has everything to prove but has no idea what ‘prove’ really means.”

Springsteen himself would agree with this assessment. Looking back on his debut in the twenty-first century, he told journalist Brian Hiatt that he felt his goal with his musical career was nothing short of the transcendental task to “summon up a world,” and that Greetings was his full-throttle attempt at doing that. Bruce had come from a noisy background, leading both a hard rock jam band and a more soulful Jersey Shore bar band, both built mostly around his guitar playing. But after a few years in the scene, he wasn’t satisfied. At 22 years old, he decided that he could never be one of the world’s best guitar players; instead, he felt that songwriting would be his key to the universe. Says Bruce, “I felt I’d been gifted with a very, very high-octane journeyman’s capabilities… and if I put those things together really, really thoughtfully and with enormous will and vitality, I can turn all of that into something that transcends what I felt my modest abilities were.”

“I was very influenced by Dylan and a lot of other writers… so I said I’m going to be a poet – I hadn’t read any poetry, but I’m going to be a poet! I was using this very intense poetic imagery, which now, looking back on it, doesn’t feel like poetry but rather an insane, crazed sort of lyricism.”

And so, Greetings. An album full of manic, machine-gun lyrics, often inscrutable metaphors, and grocery lists of proper nouns. Oh god, the nouns. You’ll meet more specifically named characters in Greetings from Asbury Park than a Tolstoy novel. One has to imagine Tolkien summoned his worlds the same way – by conjuring a bunch of fantastic names and heightened premises onto paper and filling out the details as he went. Greetings gives us a look into the world of a young New Jersey singer-songwriter elevated to the level of mythology. Bruce has a lot to share, and he’s not necessarily worried about his audience keeping pace his meter. And so, we get the album’s lead song, “Blinded by the Light.”

“Mama always told me not to look into the sights of the sun / but oh mama that’s where the fun is.” - “That was where I wanted to go. I wanted to get blinded by the light,” Springsteen told an audience at VH1 Storytellers in 2005. “I wanted to do things I hadn’t done and see things I hadn’t seen. So it was really a young musician’s tale, kind of a litany of adventures.” And with this opening track, which Mod group Manfredd Man would later obliterate while taking to number one, Bruce called us all into his adventure.

As any fantasy writer will tell you, one way to summon up a world is to build a rich mythology around it. That’s something Springsteen himself seemed to be aware of; if you ever saw him perform Greetings’ second track, “Growin’ Up,” in concert, he would often take time after the solo to tell a story, wildly exaggerated and in mythic tones, about something from his youth, specifically in relation to music. That makes sense, because “Growin’ Up” is really a mythologization of Bruce’s journey of embracing music as a means of salvation. You’ll hear it in the final verse – “I swear I found the key to the universe in the engine of an old parked car.”

“That’s what I was trying to do,” Bruce said. “I found so much in culture that was considered to be transient and trash. I felt that I heard a world of pain and pleasure and beauty and darkness, all coming out of those little records on the radio, and I knew that it was there. I wanted to find my key to that – the idea is that it’s there, even in this town, if I look hard enough.”

That’s really the key to the entire mythos of Bruce Springsteen, and certainly Greetings, right there – the idea that the entire world could be contained in one song, and that the right metaphors could unlock it. Lyrics incarnate into flesh; flesh transubstantiates into soul. Speaking about this poetic alchemy, Bruce said: “I grew up feeling… that I was broken, but that I was still magic. And that’s what you feel in this song. There’s the insistence on a certain sort of magical fantasy, almost. Which can be, at a certain moment, when you’re young, pretty life-sustaining.”

Songs sustain life. But also, if you’re good enough… songs create it.

Of course with something as ambitious as creating a world with words, sometimes things get a little messy. Characters might appear as sketches instead of souls; metaphors may don Icarus wings but fall short of transcendence, into valleys of nonsense. Sometimes you write a song in a 15-minute burst of inspiration and, although you find it brilliant and sophisticated at the time, you reconsider, only playing it twice for audiences over the next 50 years… maybe wishing you had an editor, or someone else to help shape the vision, on that one.

Despite his rock band background, Bruce conceived of most of the songs on Greetings as solo singer-songwriter pieces. The comparisons to Bob Dylan weren’t just coming from inside the house; Springsteen was part of a crop of artists, like John Prine and Loudon Wainwright, marketed as the next incarnation of the great Bobby D, which is really funny because Bob Dylan was only 30 at the time. Bruce’s manager Mike Appel described him as “a combination of Bob Dylan, Chuck Berry, and Shakespeare.” Columbia Records A&R man John Hammond said of Springsteen “he’s much further along, much more developed than Bobby was when he came to me,” pretty incredible praise.

But partway into making his debut, Bruce realized that something was missing. Columbia Records president Clive Davis realized it too. He returned the first cut of the album to Springsteen’s camp, asking for more full instrumentation. He wanted songs that could get radio play. He wanted the album to rock. And so Springsteen went back to his songwriting temple – the back of a beauty shop he lived above, which for some reason had a piano in it – and he came back with two more songs, the two songs that would become the album’s singles and the only two songs to feature the most iconic member of the E Street Band, Clarence Clemons. Indeed, it’s impossible to imagine Bruce Springsteen’s career without Clarence. Every once in a while, I guess, it pays to listen to the executives.

Despite ultimately ceding Greetings to a full-band presence, though, it’s Bruce’s lyrics, his storytelling, that truly make the album remarkable. This is by design; John Hammond and Mike Appel purposefully put the band low in the mix to not lose the singer-songwriter appeal of Springsteen. It’s easy to understand why; it was a solo guitar and vocal session that convinced Mike Appel to want to manage Springsteen, and a solo guitar and vocal session that convinced John Hammond to push for Springsteen at Columbia. At both sessions, Springsteen played a song that transfixed each man – “It’s Hard to be a Saint in the City,” the closing track off Greetings. Both men were sure that lyrics like this guaranteed that Springsteen had an audience waiting for him, if only they could be reached. There was still a lot to figure out around the career of Bruce Springsteen, but man, what a start.

So on balance, how was Greetings received? It was, it’s fair to say, a mixed bag. Dan Nooger of the Village Voice wrote “Much of the album seems to stumble under the weight of its own supposed significance and obscures the fact that he has a strong innate feel for singing hard rock.” In Creem, Dave Marsh said “His entire career is based upon a total disregard for taste and control on the most fundamental level.” Dave Marsh would go on to become Bruce Springsteen’s biographer.

It wasn’t all bad, though. When Rolling Stone finally covered the album six months after its release, legendary critic Lester Bangs wrote a hell of a review that included the following:

“He’s been influenced a lot by the Band, his arrangements tend to take on a Van Morrison tinge every now and then, and he sort of catarrh-mumbles his ditties in a disgruntled mushmouth sorta like Robbie Robertson on Quaaludes with Dylan barfing down the back of his neck.”

But “what makes Bruce totally unique and cosmically surfeiting is his words. Hot damn, what a passel o’ verbiage! He’s got more of them crammed into this album than any other record released this year, but it’s all right because they all fit snug, it ain’t like Harry Chapin tearing rightangle malapropisms out of his larynx. What’s more, each and every one of ’em has at least one other one here that it rhymes with. Some of ’em can mean something socially or otherwise, but there’s plenty of ’em that don’t even pretend to, reveling in the joy of utter crass showoff talent run amuck and totally out of control.”

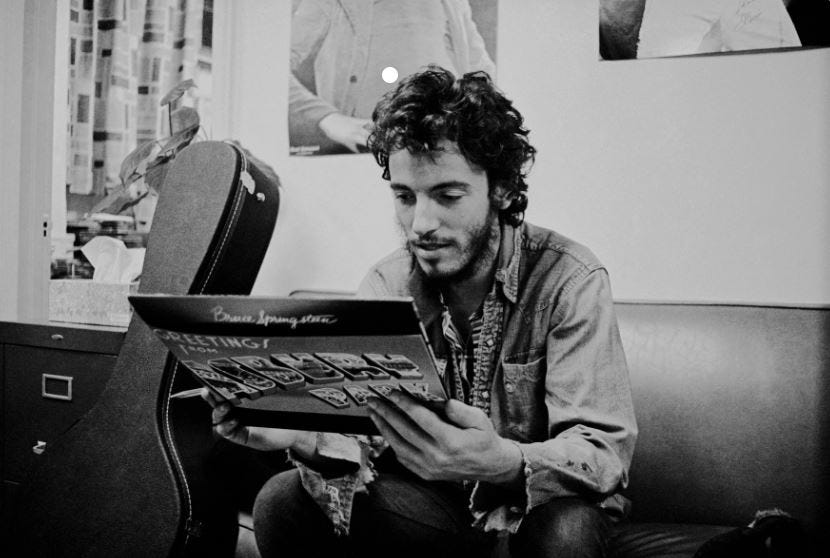

Bangs concluded that Greetings was “breathtakingly complicated.” “You might think it’s some kinda throwback, but it’s really bracing as hell because it’s obvious that B.S. don’t give a shit. He slingshoots his random rivets at you and you can catch as many as you want or let ’em all clatter right off the wall which maybe’s where they belong anyway. Bruce Springsteen is a bold new talent with more than a mouthful to say, and one look at the pic on the back will tell you he’s got the glam to go places in this Gollywoodlawn world to boot. Watch for him; he’s not the new John Prine.”

So there’s that.

Of course, the magic of hindsight illuminates more about Greetings from Asbury Park than even Lester Bangs could. In the flood of this week’s numerous 50th anniversary retrospectives on the album, a couple pieces get to the human heart of the album beating underneath all those words. Marc Myers in the Wall Street Journal: “What’s most fascinating about Greetings is its earnest compassion for free-wheeling losers…. There are no villains, only lost souls….” Above all else, this empathy for his characters, his universe, is the surest hallmark of Springsteen’s writing, and even on an album as manic as Greetings from Asbury Park, it’s on full display. That’s likely what prompted Marc Myers to conclude “Mr. Springsteen’s future was still uncertain on Greetings, allowing us to feel both his optimism and his vulnerability. In this regard, the LP plays like a postcard from his unsteady self.”

And, building off that, Jeremy Levine from Albumism again: “It fills your spirit in a way that no other work can. I don’t think of it as the start of a journey. I think of it as a journey not yet begun, the sound of home.”

Even though not everyone was ready for this journey in 1973, there’s no doubt that Bruce Springsteen conjured up a hell of a welcome to his world on his debut record. And he did it by looking within. Greetings is Bruce – his friends, his lovers, his aspirations, his desires, his overwrought metaphors, his home. In an effort to replicate the magical lyricism of Bob Dylan, Springsteen reached inside himself and unlocked an entire universe in just a few thousand words. And even though, on future albums, he would write more confidently, and find more success, there truly is something magical about an artist with a burning desire and zero discipline. Greetings from Asbury Park isn’t Springsteen’s masterpiece, but in a way, it’s his most ambitious record.

And — to insert myself here — that’s why I find Greetings inspirational. There’s a message here about just going for it that all of us with creative aspirations could stand to internalize. Don’t worry about form, discipline, critical response, or looking like a madman. Just make stuff. You never know what’s going to happen. What you make might suck, and — with some help from the public — you might decide it’s not for you. Maybe in six months, someone will write that something you anguished over for years sounds like Bob Dylan barfing down the back of your neck. But maybe, two years later, you’ll come back with one of the greatest albums of all time. I mean, realistically, probably not. But wouldn’t it be fun to try?

Sources

Lester Bangs, Rolling Stone: “Greetings From Asbury Park, NJ”

Brian Hiatt, Bruce Springsteen: The Stories Behind the Songs

Jeremy Levine, Albumism: “Bruce Springsteen’s Debut Album ‘Greetings From Asbury Park, N.J.’ Turns 50 | Album Anniversary”

Marc Myers, The Wall Street Journal: “Bruce Springsteen’s ‘Greetings From Asbury Park, N.J.’ Turns 50”

Ryan White, Springsteen: Album by Album